Persan Beaumont

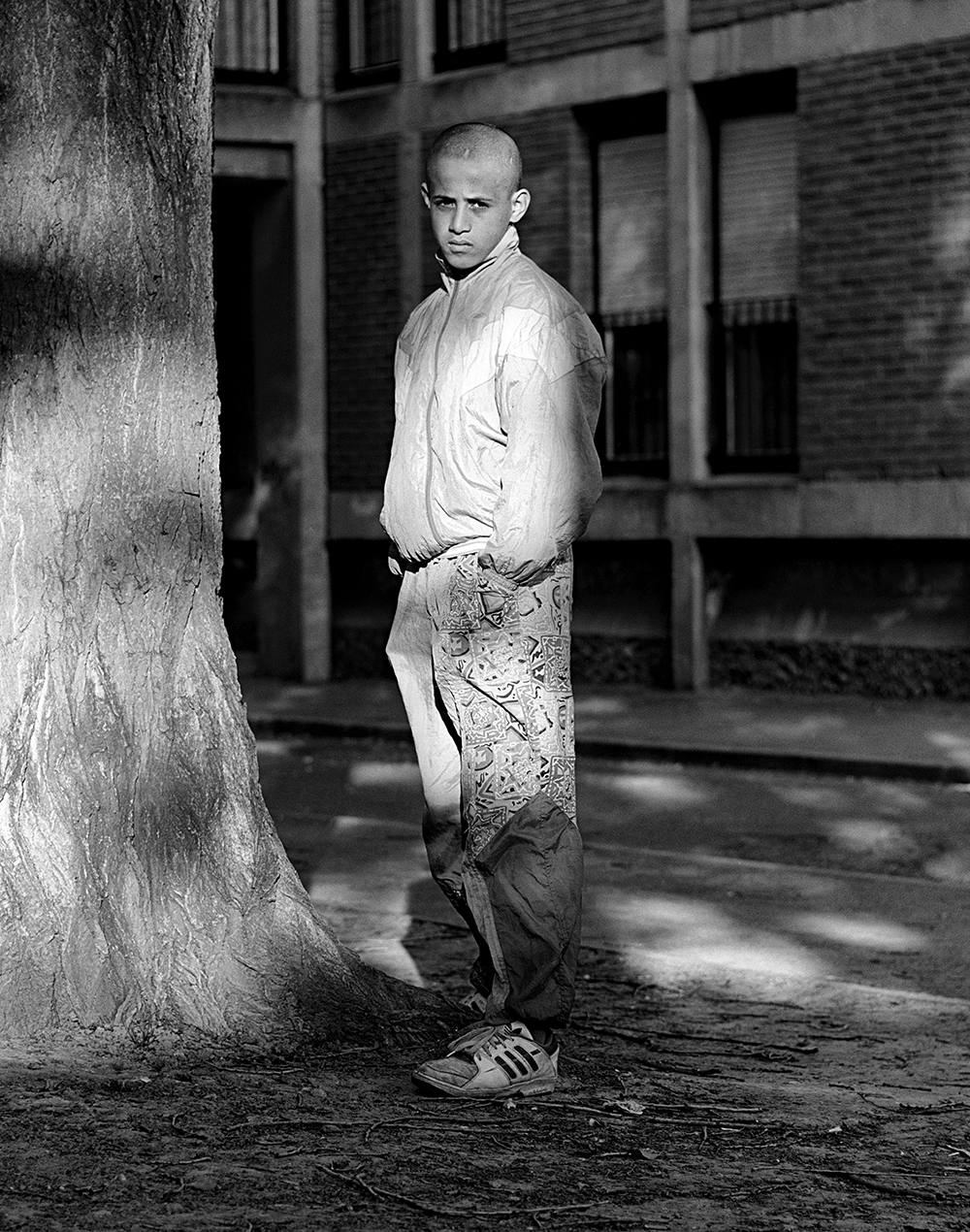

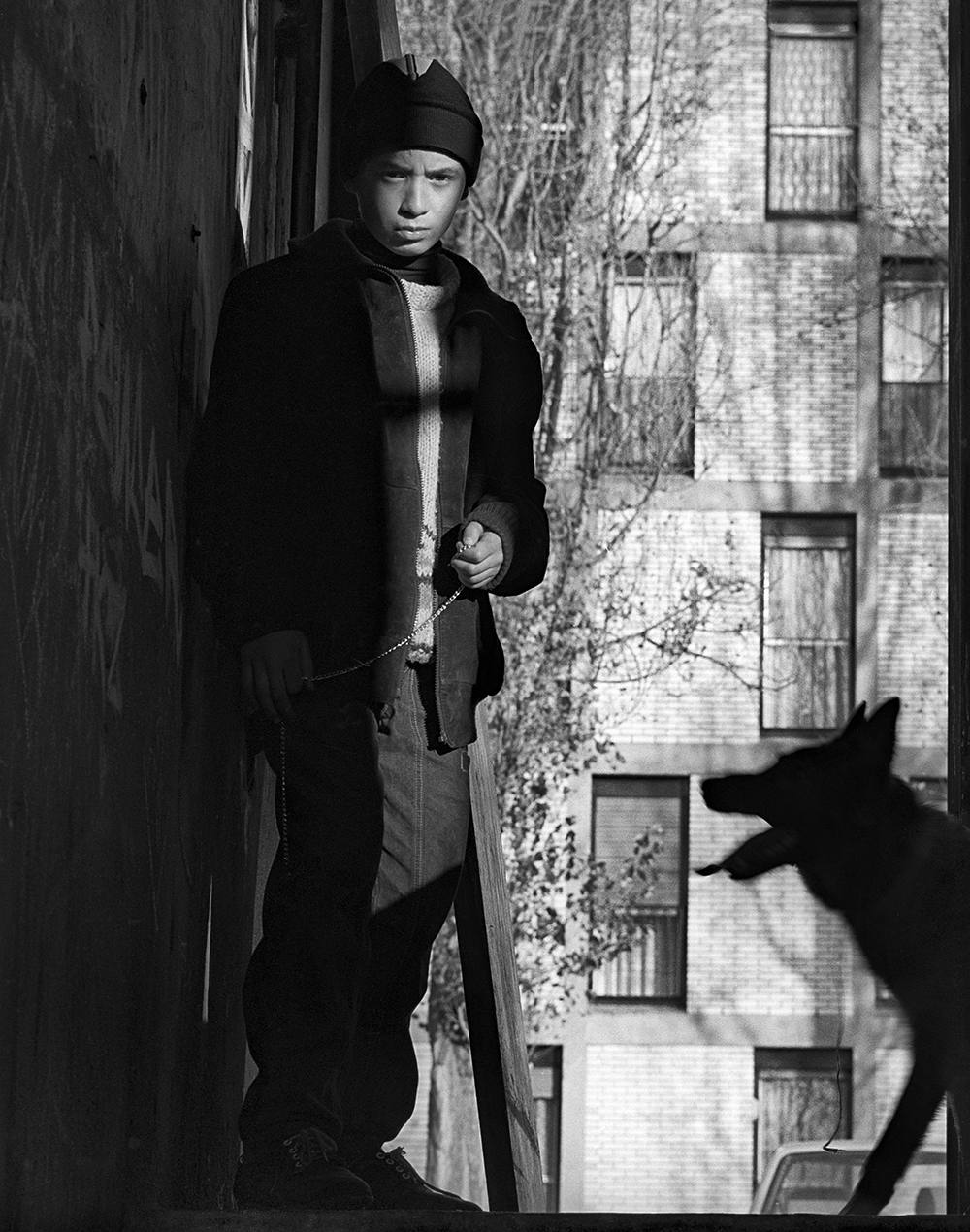

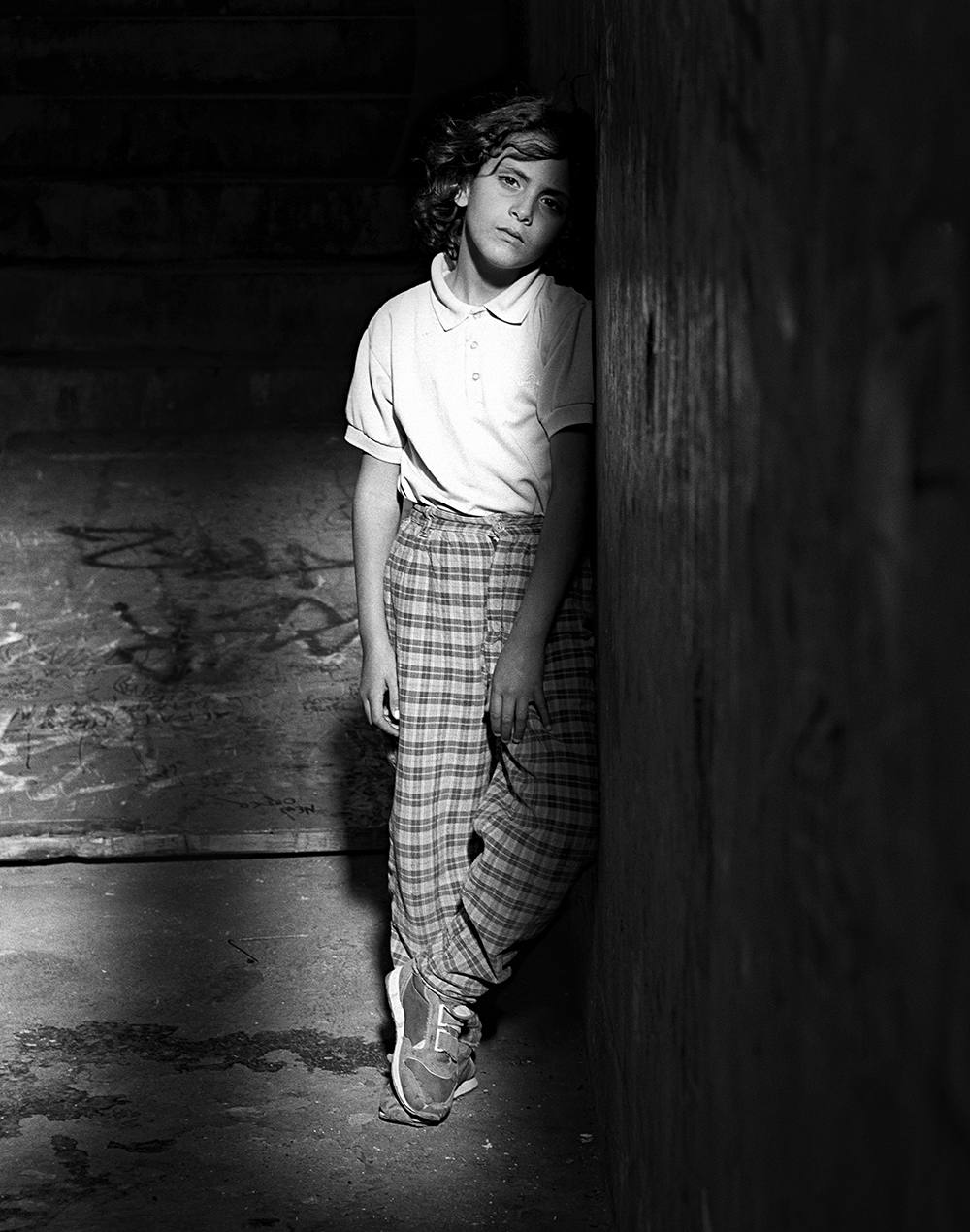

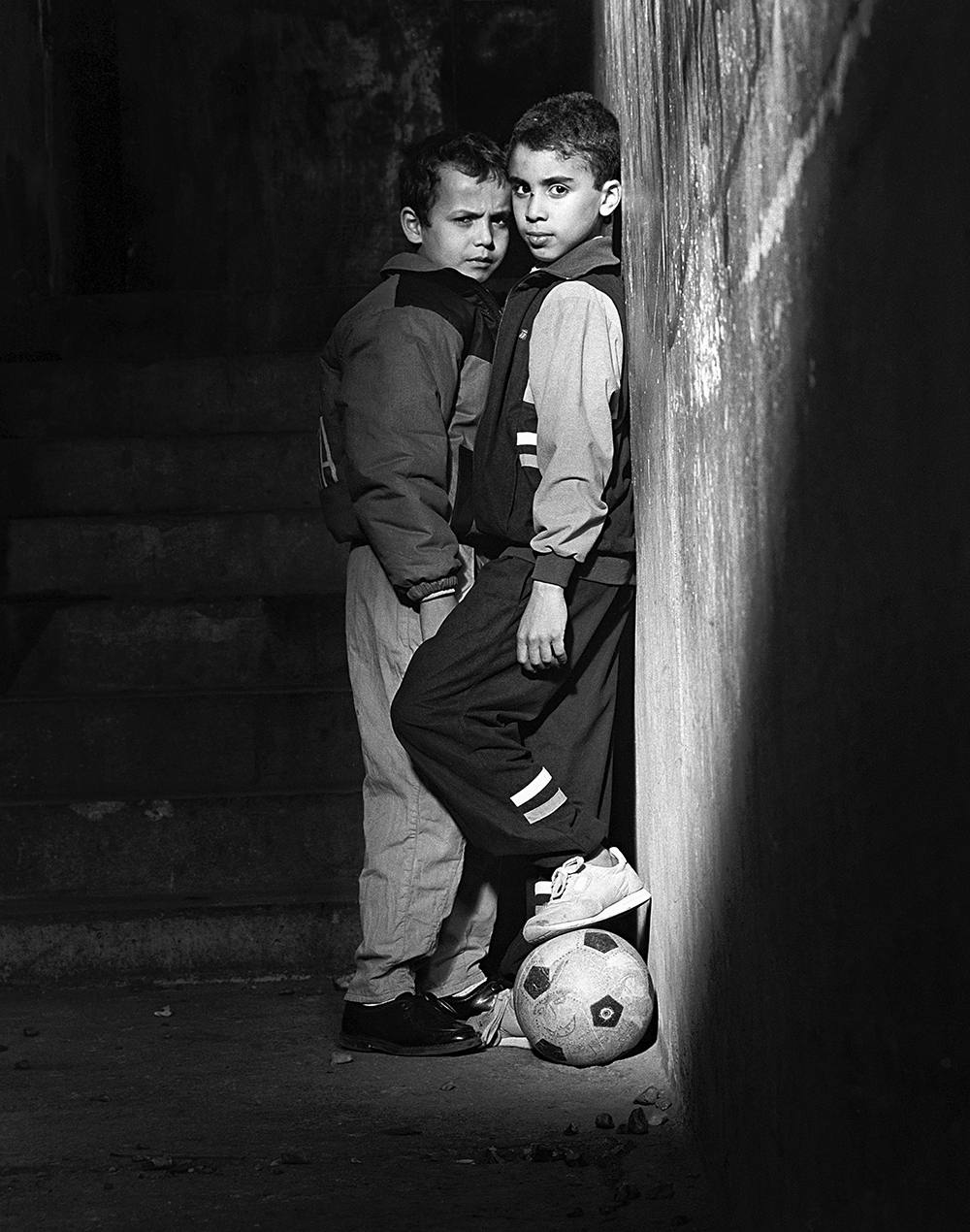

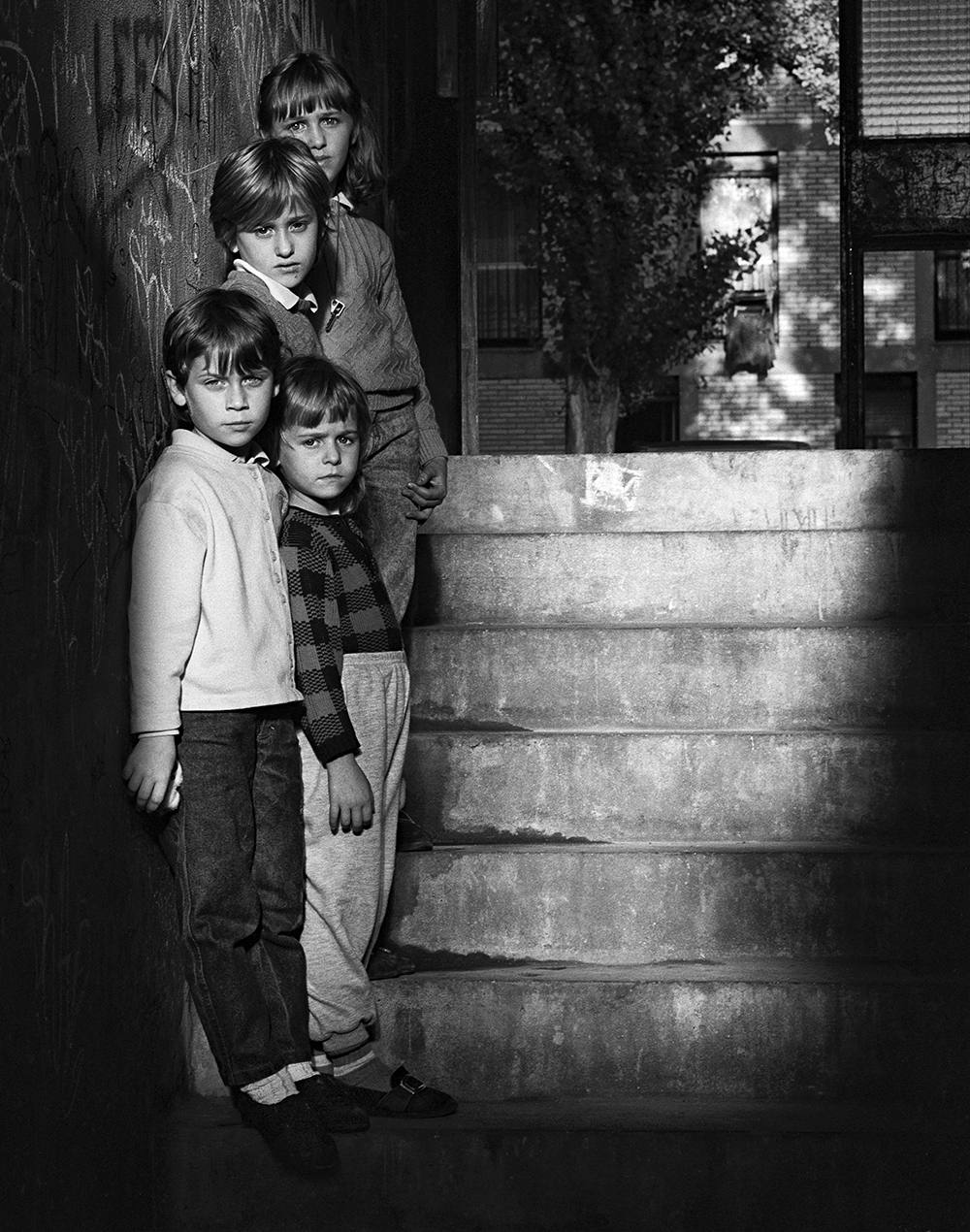

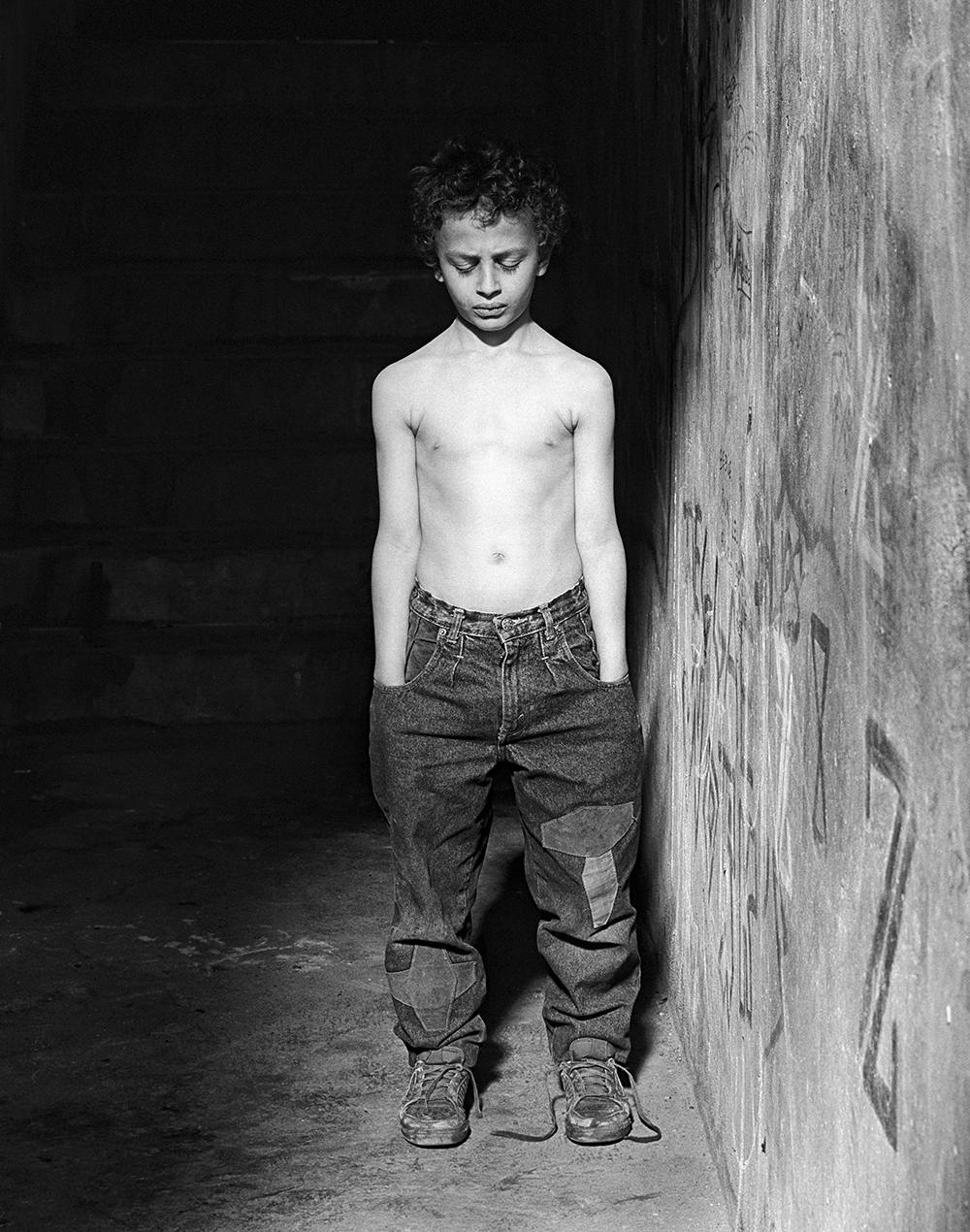

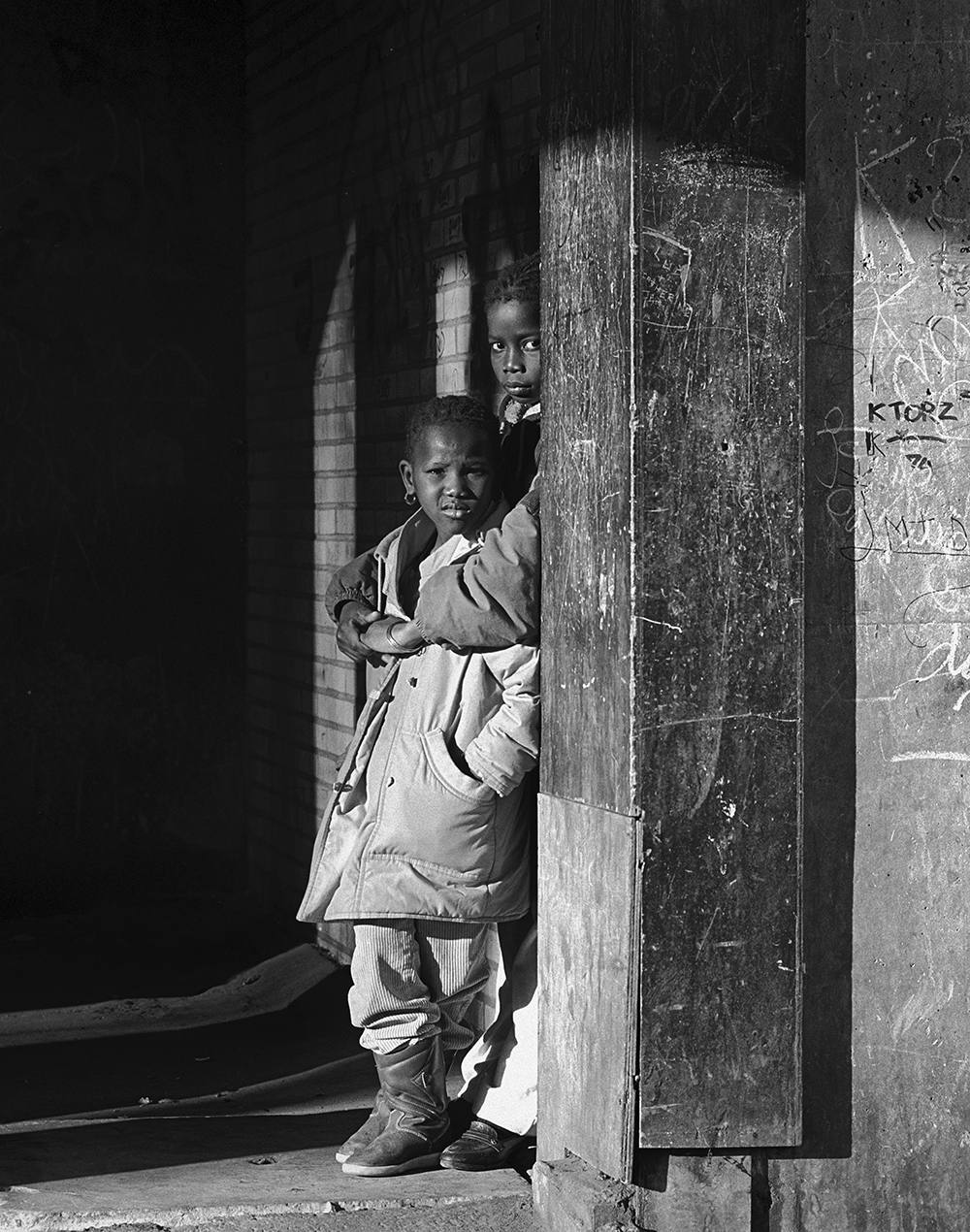

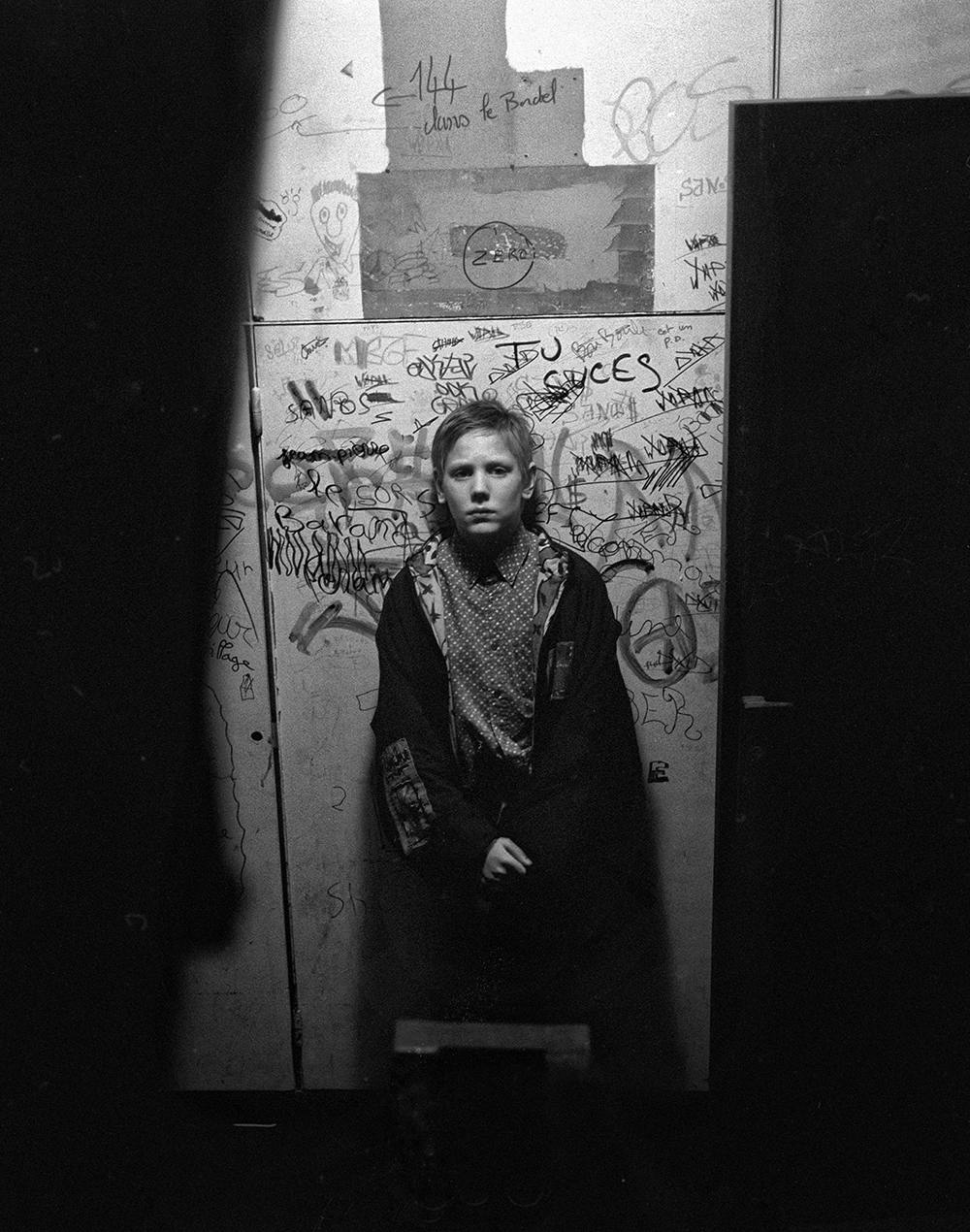

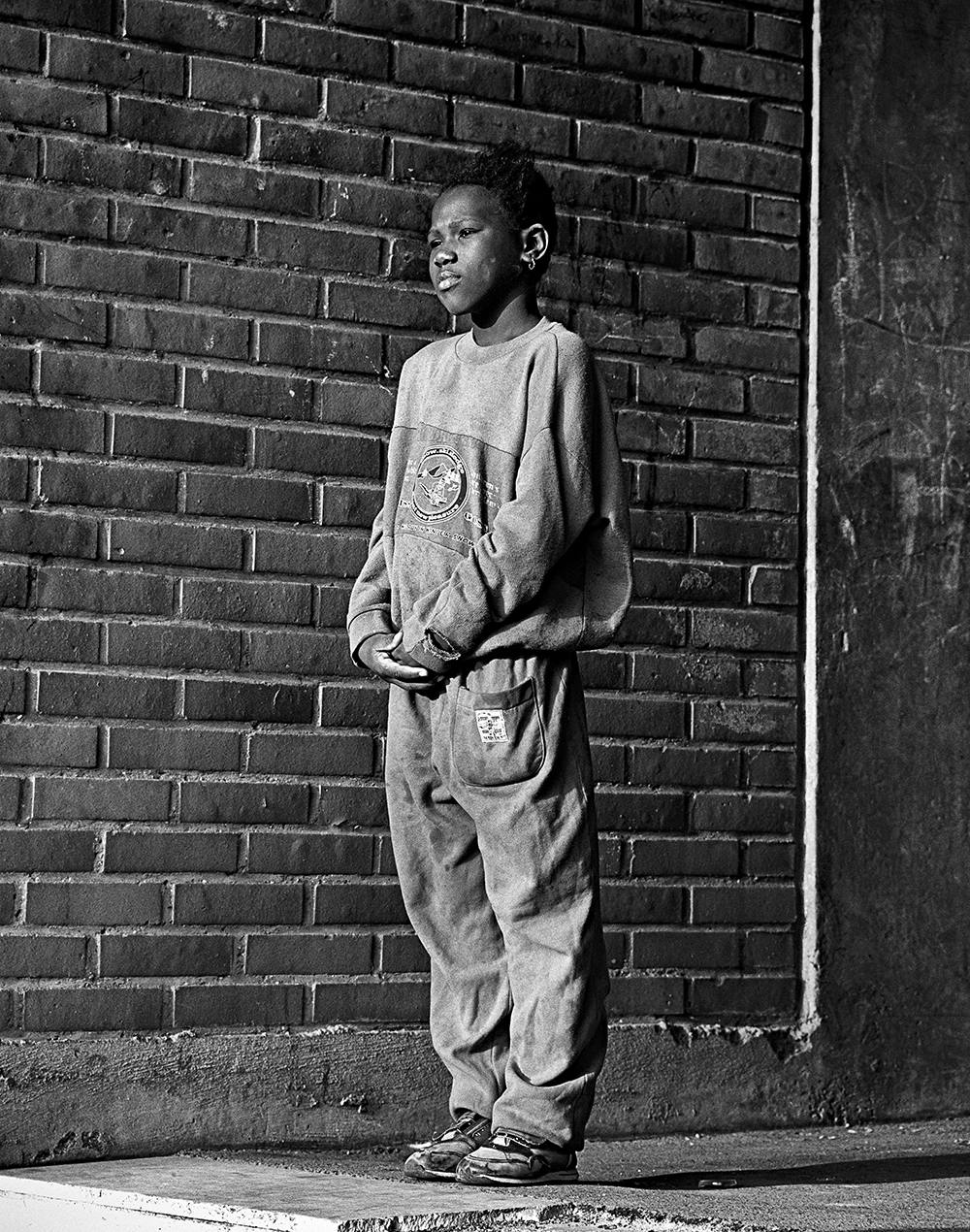

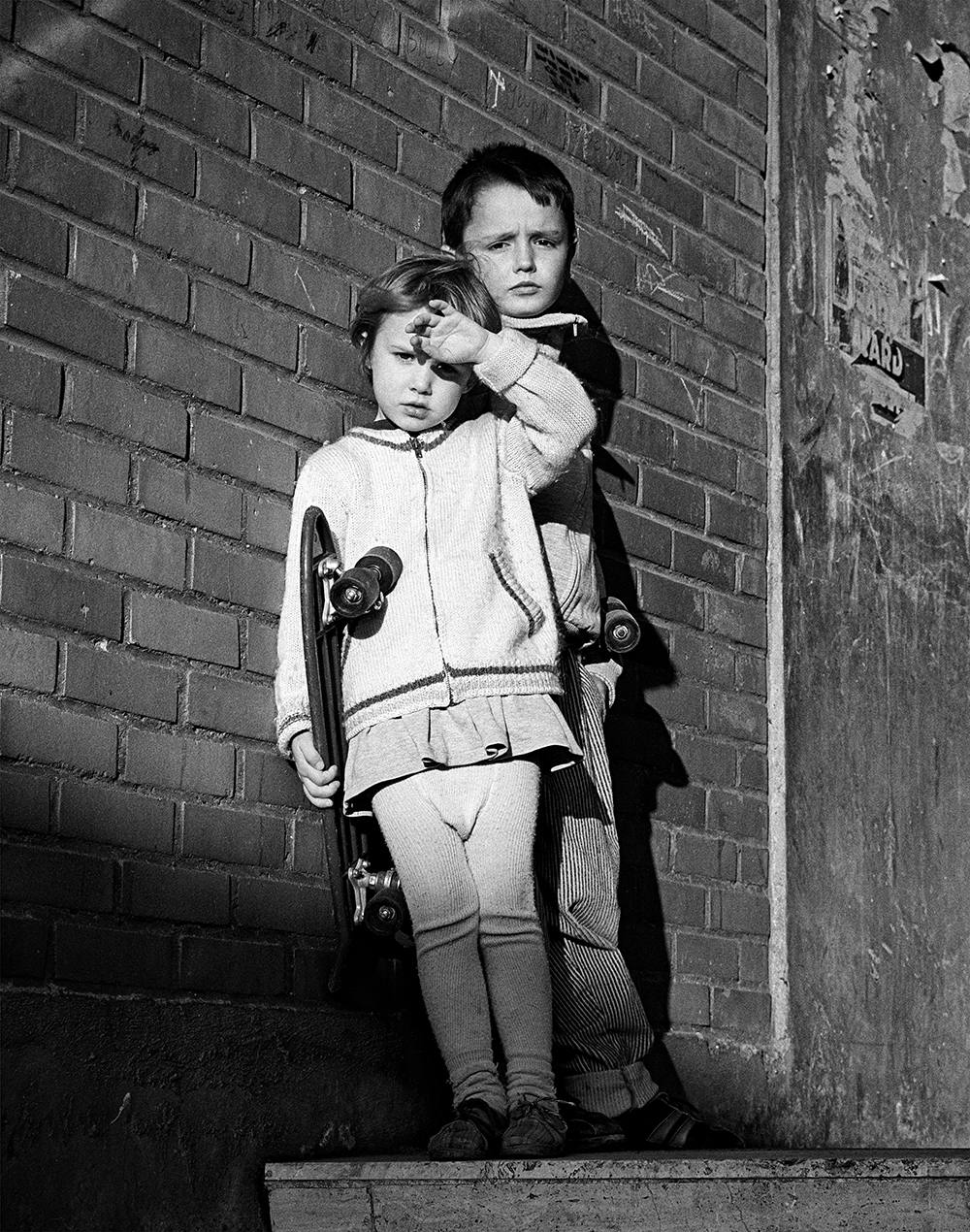

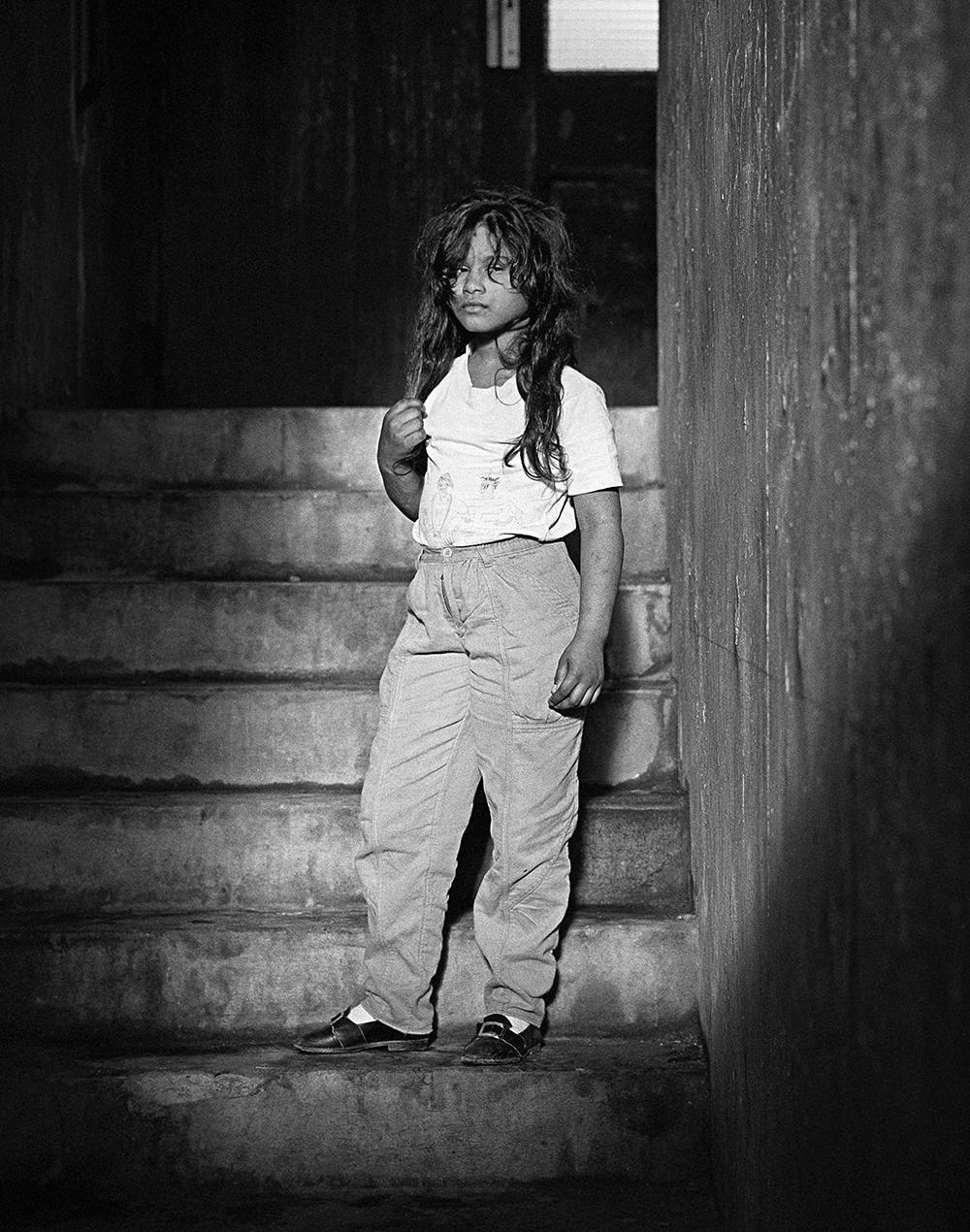

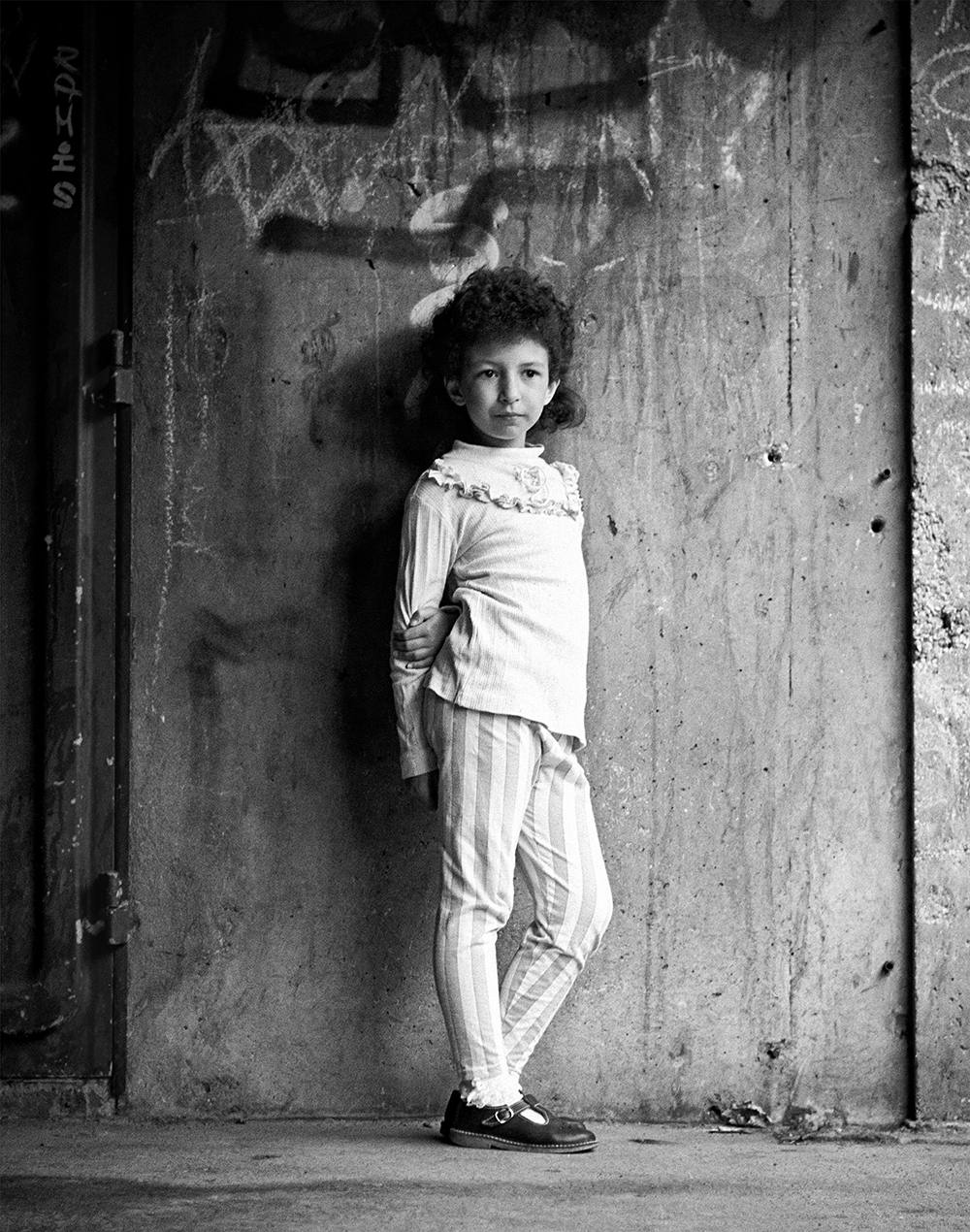

Coming back from my village, where I had, during summer, photographed its inhabitants, and among them my great-aunt Juliette, I met in the train some boys from an estate called “le Village” in Persan, a small suburban town from the Val d’Oise, north area of Paris. They were about ten, who had spent a few days vacation in Les Sables d’Olonne. They were ambling about the train from car to car with a cassette player playing rap without anybody addressing them. I used to live inside Paris and for some time, I had the idea of documenting my day-to-day life. From my first day, I had understood that, if I had been settling by the time of les Halles and of small cafés, I would have loved this town, but Paris had already started to reject popular population towards its suburbs. Nonetheless, I kept on my wish, and thought that, if I moved to a suburb, I would find there more spontaneity. The opportunity came as I crossed this group of suburban youngsters in the train, after we had a chat. I showed them the pictures of Juliette and I remember that when seeing them they found them “classy !” . And precisely at that point, I asked them whether they would agree if I meet them in their housing estate. Coco gave me his telephone number. At that time, one spoke rarely about problems of the suburbs, but it was not without some apprehension, that at the beginning of 1987 fall, I finally decided to call Coco. He gave me an appointment for the next sunday at the Persan-Beaumont station. For the first time, I went to the Gare du Nord to take a train which took me to what was still for me a totally unknown world. Persan-Beaumont was then the end station of the suburban train, and when I got my nose out, there was a group of young boys waiting for me, mainly composed of French boys of North-African origin. We walked to the building Nr 14 which was the head-quarter of the estate. I took pictures, portraits, but I quickly realized that I was unable to immortalize this generation of growing rap, of which I did not know any of the codes. They put themselves on stage and I was absolutely not satisfied of my pictures. It’s only when I started to photograph their little brothers and sisters that I knew, I got something. The relaxed behaviour of kids revealed in a dazzling manner the difficulty I had to live my isolation. There was a kind of chemistry between their trust and my sadness. I went there during five years, always on sundays afternoons, about maybe once a month. I had succeeded to be at the end part of the place. It was then on a sunny day, when a man who seemed slightly drunk, got out of his car to ask me for my papers. He got back in, angry, after I refused to show them. The children, who observed the odd scene, came to me laughing to tell me that the man was the mayor of Persan. A few months later, this elected communist lost his town hall in favor of the right, still in place today. In the following years the problems of suburban estates would become a crucial stake, subject of debates and reports. But I must recognize that, at that time, much more than by political conviction, I had come there to do this work to save my life.

C’est en rentrant de mon village, où durant l’été j’avais photographié ses habitants et parmi eux ma grand-tante Juliette, que j’ai fait la connaissance dans le train Corail des garçons de la cité « Le Village » à Persan, petite commune du Val-d’Oise. Ils étaient une dizaine et avaient passé quelques jours de vacances aux Sables-d’Olonne. Ils déambulaient de wagon en wagon avec un radiocassette qui diffusait du rap sans que personne ne les interpelle. Je vivais à Paris et depuis quelque temps j’avais l’idée de documenter mon quotidien. Dès mon arrivée, j’avais compris que, si je m’y étais installé du temps des halles et des bougnats, cette ville m’aurait enchanté ; mais Paris avait déjà commencé à rejeter les couches populaires à sa périphérie. Néanmoins, mon désir persistait et je me disais que si j’allais en banlieue j’y trouverais plus de spontanéité. L’occasion s’est présentée lorsque j’ai croisé cette bande de jeunes banlieusards dans le train et que nous avons discuté. Je leur ai montré les images de Juliette et je me souviens qu’en les voyant ils ont dit « Classe ! ». Et c’est à ce moment précis que je leur ai demandé s’ils étaient d’accord pour que j’aille les rencontrer dans leur cité. C’est Coco qui m’a laissé son numéro de téléphone. À cette époque on parlait très peu des problèmes de banlieue mais ce n’est pas sans une petite appréhension qu’au début de l’automne 1987 je me suis enfin décidé à appeler Coco. Il m’a donné rendez-vous le dimanche suivant à la gare de Persan-Beaumont. Pour la première fois, je suis allé gare du Nord prendre un train qui m’a emporté vers ce qui était encore pour moi un monde totalement inconnu. Persan-Beaumont était alors le terminus du train de banlieue et, quand j’ai mis le nez dehors, m’attendait un comité de jeunes garçons, composé en majorité de Français d’origine maghrébine. Nous avons marché jusqu’au bâtiment numéro 14 qui était le point de ralliement de la cité. J’ai fait des photos, des portraits, mais j’ai vite réalisé mon incapacité à immortaliser cette génération du rap naissant dont je ne connaissais aucun des codes. Ils se mettaient trop en scène et je n’étais absolument pas content de mes images. C’est seulement quand j’ai commencé à photographier leurs petits frères et sœurs que j’ai su que je tenais quelque chose. Le lâcher-prise des enfants a révélé de façon fulgurante ma difficulté à vivre mon isolement. Il y avait comme une alchimie entre leur confiance et ma tristesse. J’ai effectué le trajet durant cinq années, toujours le dimanche après-midi, à raison peut-être d’une fois par mois. J’avais fini par faire partie des lieux. C’est par une belle journée ensoleillée qu’un homme, semblant légèrement ivre, est sorti de sa voiture pour me demander mes papiers et qu’il y est remonté en colère après mon refus de les lui montrer. Les enfants qui avaient observé cette scène étrange sont venus me dire en riant que l’homme était le maire de Persan. Quelques mois plus tard, cet élu communiste perdait sa mairie au profit de la droite, à ce jour toujours en place. Dans les années qui suivraient, les problèmes des cités deviendraient un enjeu crucial, le sujet de débats et de reportages. Mais je dois reconnaître qu’à l’époque, bien plus que par conviction politique, j’étais venu faire ce travail pour sauver ma peau.